The arrests

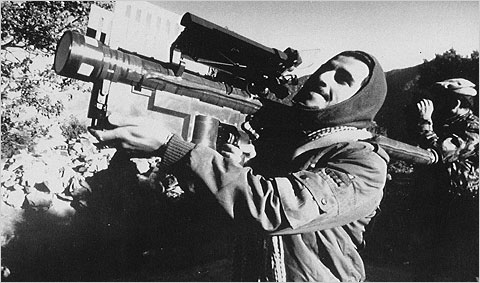

Wednesday night of four men in New York on their way to an Air

National Guard base with what they thought was a working Stinger

missile reminds your Lede blogger that de spite periodic warnings

that terrorists might try to shoot down commercial jets using

shoulder-fired missiles, only one such attack has even been tried in

recent years. (Luckily, the New York plotters had been given an

inoperable Stinger by someone secretly working with the Federal

Bureau of Investigation.)

In November 2002, a

failed attempt to shoot down a Boeing 757 operated by an Israeli

airline just after it took off from an airport in Kenya prompted a

number of alarming reports in the American media. According to those

reports, there were a

large number of these weapons in circulati on. For years,

intelligence officials had described them as so

easy to use that firing a Stinger was compared with operating “a

point-and -shoot camera.”

Those factors led to a

lot of discussion, in the aftermath of the attack in Kenya,

about the possible need to equip

civilian jets with devices like those used on military aircraft to

fend off missiles. There were also calls to secure

the perimeters of America’s airports, since a federal task force

found that passenger planes “would be vulnerable to attack by

terrorists using shoulder-fired missiles” during take-off and

landing. One would-be pundit even proposed redirecting commercial

air traffic nationwide to impose no-flight

zones over major cities.

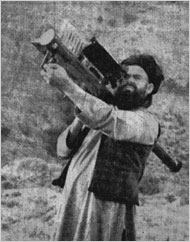

Anyone who read and semi-obsessed over these many articles detailing

the threat from these weapon s will also recall that several

hundred Stingers were reportedly left in the hands of the Afghan

holy warriors supplied by the C.I.A. in the 1980s. In 2002, the

Bush administration said Al Qaeda “planned to position”

Stingers, or similar Chinese- and Russian-made SA-7 missile systems

they had trained with, “around the globe.”

So, if this weapon is so powerful and easy to get, why has there

been no wave of terrorist attacks on commercial jets? We called

someone who might know, Milt Bearden, a retired senior C.I.A.

official who ran the agency’s operations in Afghanistan during that

country’s war with the Soviet Union in the 1980s. Mr. Bearden told

The Lede that the fear of terror attacks with Stingers is nearly two

decades old. “When TWA Flight 800 went down, everyone went nuts,” he

recalled, as speculation was rampant that the

jet might have been shot down with a Stinger missile. After

investigators discarded that theory, most Americans forgot about the

shoulder-fired missiles.

Even so, as Steve

Coll wrote in his book “Ghost Wars,” the C.I.A. spent quite a

bit of money buying back as many leftover Stingers as possible from

Afghan warlords during this period, precisely because of the fear

that they might be used against American planes:

After the Soviet troops left, the C.I.A. fretted that loose Stingers would be bought by terrorist groups or hostile governments such as Iran’s for use against American civilian passenger planes or military aircraft. Between 2,000 and 2,500 missiles had been given away by the C.I.A. to Afghan rebels during the war. Many had gone to commanders associated with anti-American radical Islamist leaders [...]Pakistan’s intelligence service handled most of the repurchases on a subcontract basis for the C.I.A. earning an authorized commission for each missile collected [...]The total cash spent by the C.I.A. on Stinger repurchases during the mid-1990s rivaled the total cash donations by other sections of the U.S. government for other humanitarian assistance in Afghanistan during those years by the American government.

In December 2001, Slate

reported that “the Pentagon stated that some 200 to 300 of these

U.S. -made shoulder-launched surface-to-air missiles remained in

Taliban and Al Qaeda hands.” So what happened to them?

According to Mr. Bearden, they are probably just too old to work

properly by now. “The last ones were delivered in 1988,” he told The

Lede, “and its a pretty complex system — a lot of things can go

funky” in 21 years. As for the similar, but older and less advanced

SA-7 model made first by the Soviets, and deployed in the failed

attack in Kenya, he said, “It’s just not a very good weapon.”

Another possible explanation is simply that Stingers and other

shoulder-fired missiles have been used by Islamic militants, but

against American military targets rather than civilian ones. In

Afghanistan and Iraq, reports on the exact causes of helicopter or

jet crashes are hard to come by. In a

recent blog poston the Washington Note, Col. Lawrence Wilkerson,

who was chief of staff to former Secretary of State Colin Powell,

suggested that 200,000 American troops in Iraq and Afghanistan

0present a far more lucrative and close-proximity target for Al

Qaeda than the United States20homeland.” It is certainly possible

that shoulder-fired missiles have caused some of the nearly 5,000

American deaths in those wars.

Another factor might be that sting operations, like the one that

provided the four New Yorkers with a non-working Stinger, are at

least somewhat effective disrupting the trade in these weapons.

Since at least 1990, there have been reports of the F.B.I. breaking

up plots to smuggle Stingers to I.R.A.

guerrillas,Colombian

drug lords and arms

dealers who might have supplied them to terrorists.

Finally, there is of course the

chilling possibility raised by Scott Shugerwriting for Slate in

late 2001 that militants might20simply be still “lying in wait,” for

the right opportunity to shoot down civilian jets and cause chaos.

Mr. Shuger wrote eight years ago:

If I were the last Al Qaeda fighter with a Stinger left in Afghanistan, with the same willingness to die exhibited by the 9/11 gang, I might wait in the weeds — even until long after the war is “over” — for an American plane landing with food packages or a U.S.O. troupe or a delegation from Washington.